Little Helen. That's my grandma to the left. She will be 90 years old on June 23.

Little Helen. That's my grandma to the left. She will be 90 years old on June 23.

This photo was taken of her when she was very young, maybe three or four years old.

She's sitting perched atop a lush fur blanket, legs crossed demurely at the ankles, wearing her best dress. My grandma grew up in Brooklyn, where her dad (at the time this photo was taken) was a furrier. Legend has it that Little Helen once owned a tiny coat made of ermine.

But the family was always poor, and like other recent immigrant families, my grandma's father had a variety of jobs. He later became a grocer. Perhaps the Depression killed off the furrier business, I don't know. Little Helen worked hard as a child to help earn money for her family. I remember her talking about doing piecework after school, gluing ribbons and decorations on cards. She gave her meager earnings to her mother.

The photo was for a Beautiful Child Contest, and she won. I think my grandma and her parents receieved a small cash prize of $5.

My grandma has always been a little girl, in stature and in heart. She takes pleasure in the tiny, simple things, like a child, and she also worries about everything. She can be very stubborn and also extremely sensitive and emotional. I think being a child of the Depression took more of a toll on her than perhaps on some other people. There is a part of her that still seems shadowed by the threat of poverty, of some vague loss.

When she is upset or worried, sometimes you can distract her with a new story told with a lot of enthusiasm or some show-and-tell, just like you would a six-year-old with a sparkler.

***

Last week, my grandma ended up in the hospital and she missed the birthday party. Of all of the people not to be there, that was the cruelest blow. She lives for Little Curly Girl. Because she was in the ICU, we couldn't take Little Curly Girl to see her either and there was no phone near her bed to even call.

Last week, my grandma ended up in the hospital and she missed the birthday party. Of all of the people not to be there, that was the cruelest blow. She lives for Little Curly Girl. Because she was in the ICU, we couldn't take Little Curly Girl to see her either and there was no phone near her bed to even call.

First we got really terrible news from one doctor. And then we got much better news from the second doctor, who concurred with my grandma's old cardiologist. The first doctor, with his dire predictions and perfunctory manner, sent the entire family into an emotional tailspin on Sunday night, only for our hopes to be revived when he went off duty and all of his conclusions were quietly moderated for the better by the new cardiologist on duty.

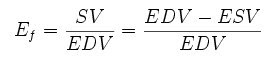

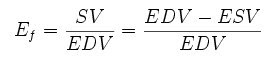

In evaluating her condition, the doctors try measure the amount of blood her heart can pump out, which is called an ejection fraction.

A normal heart's ejection fraction is 50% or better. My grandma's is between 35%-40% but that other doctor told us it was only 20%, which scared the crap out of us.

***

When we first saw grandma in the bed, she was sleeping soundly, her chest rising and falling quickly, looking almost like she was panting. Her mouth drooped, her lower teeth were askew. Her face looked pale, almost like it was covered in a fine powder. We didn't want to wake her, so we just watched her, for the better part of an hour, and mimed and signed and whispered to each other.

One of the nurses came in to wake her up to give her her medication: the tiniest chip of a pill you ever saw in your life, and some orange liquid that looked like soda but had potassium in it. My grandma awoke, hair afluff like little downy feathers all over. She looked surprised, puzzled and happy to see my mom, my sister and I seated around the bed. "Did you just get here?" she wanted to know. You could see the happiness building up in her inside: the color came back to her cheeks and lips, bringing pinkness to her face.

Grandma would not take her medicine. She had every reason in the book not to do it, just like the little kid who wants a glass of water, wants a story, has to go to the bathroom in order not to have to go to sleep. The nurse said she would come back in a few minutes to make her take it. She kept coming back and my grandma kept dilly-dallying. Grandma flirted with the handsome doctor who came in to examine her, complained that the orange soda stuff was too sour and made everyone else taste it. We told her not to be such a baby, that it wasn't that bad.

It was funny, like bad little kid funny, but after a while she really did need to take her meds and we could see that we were encouraging her misbehavior. Finally my sister and I instituted Tough Love on her, and we turned our backs on her and wouldn't talk to her until she drank everything down. She did, with a grimace. The gig was up.

***

Grandma got released from the hospital yesterday, and sounds as good as new on the phone. She's staying with my mom, and Little Curly Girl and my sister are still there so Grandma couldn't be happier. I called her this morning and she's watching her two-year old great-granddaughter eat bits of sunny-side-up egg, and putting jam on her toast. "All by herself!" she tells me. "That little girl is so smart!" I hear Little Curly Girl squealing in the background, obviously doing something exciting, which may or may not have involved jam.

"I love her so much," my grandma tells me. "That little girl is like my food. I could just eat her up."

What the doctors can't measure is the ejection fraction of love. No matter what tests they do on her, Grandma's heart will always be loving us at 100% of capacity.

***

Keep getting better, grandma. Big and little girls are expecting that.

I now have a new camera. One of these photos was taken with the new one, and one with the old (which I'm now calling the Security Blanket Camera). I'm happy using both as I learn my way and how my camera influences my style and what I'm capable of capturing images of. I know I'll need more lenses to do what I want to do but already I can see the quality of photos improve from having a larger sensor. I love being able to control the depth of field, something I was never able to do before.

I now have a new camera. One of these photos was taken with the new one, and one with the old (which I'm now calling the Security Blanket Camera). I'm happy using both as I learn my way and how my camera influences my style and what I'm capable of capturing images of. I know I'll need more lenses to do what I want to do but already I can see the quality of photos improve from having a larger sensor. I love being able to control the depth of field, something I was never able to do before.